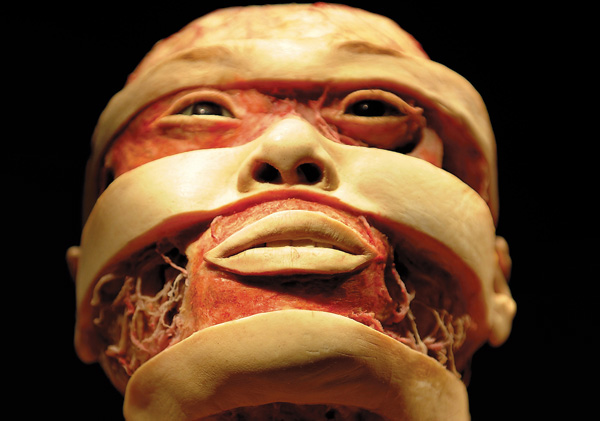

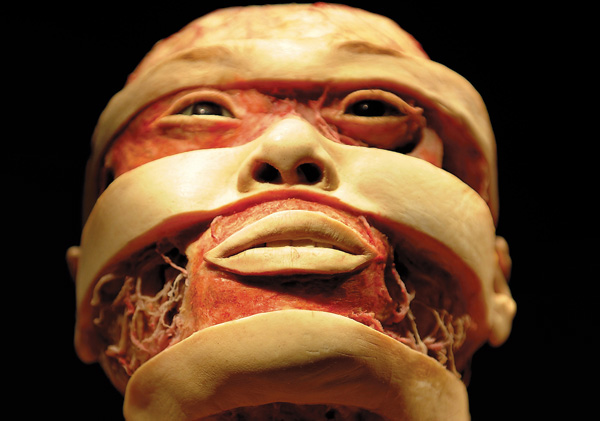

A plastinated human head is part of a “Bodies” exhibit in New York.

Timothy A. Clary, AFP, Getty Images

I filled out my consent form to donate my body for plastination, and then carried the form around with me for two weeks. I checked the yes box, “I agree that my plastinated body may be used for the medical enlightenment of laypeople and, to this end, exhibited in a museum.” I will be immortal, I imagined, in Gunther von Hagens’s “Body Worlds"—a skinless anatomical écorché for all to see. I hadn’t originally planned an illustrious posthumous career, but von Hagens’s Institute for Plastination played just the right pompous note for me when it printed Immanuel Kant’s enlightenment slogans on its brochure: “What can I know? What should I do? What may I hope for? What is man?”

The brochure assured me that having my dead body frozen and bathed in acetone, and my tissues “impregnated” with silicone, would be a triumph of reason over superstition and put me in a long tradition of principled scientific altruism. The testimonials of other donors sprinkled throughout the brochure echoed one young man’s selfless impulse: “I want to make myself useful, even after death.”

The last step in the bequeathal process was to have a family member sign the donor form. But it was at that point that I began to change my mind. “Body Worlds” (all eight versions) have become the most successful traveling exhibits in the history of science museums. Von Hagens invented his corpse-preservation technique in the 1970s at the University of Heidelberg, and started his museum tours in 1995, subsequently showing his macabre collection to over 32 million people.

In the end, I couldn’t send my donor form because I feared that my family might see my brightly colored, flayed corpse riding a plastinated pony, posed on a tightrope in Las Vegas. Or stretched out to twice my size, juggling bowling pins, riding a unicycle at the Museum of Science and Industry here in Chicago.

The aesthetic of “Body Worlds"—somewhere between Jeff Koons and velvet Elvis paintings—seemed entirely wrong for my final act. And even von Hagens seems to know that family members should not see their loved ones in such spectacle, else his brochure wouldn’t spill so much ink reassuring the donors that their pickled cadavers will be totally unrecognizable. I don’t want my own son to stumble upon me, like the Inuit boy Minik, who reportedly happened upon his own father’s skeleton in a display case at the American Museum of Natural History.

Minik and his father, Qisuk, natives of Greenland, had been coaxed back to New York as living specimens by the Arctic explorer Robert Peary in 1897. The Inuits were living in the basement of the museum when Qisuk died of tuberculosis. The boy pleaded for a proper burial, and one was staged for the boy’s benefit, but some time later Minik supposedly bumped into his father’s skeleton in a public display case. Qisuk didn’t actually make it home for proper burial until 1993.

Not everyone shares my squeamishness about family corpse display, of course, and some folks see preservation as a strengthening of filial sentiments. Pet owners, like my grandfather, pose their beloved dead pets and freeze-dry them for continued living-room habitation. But a more impressive example is Martin Van Butchell, who in the 1770s asked his friend John Hunter—the undisputed da Vinci of preservation—to pickle Van Butchell’s dead wife. Hunter obliged, and Van Butchell displayed his morbid curio in the drawing room of his home, until his new wife finally forced him to donate his old beloved to the Royal College of Surgeons, where a German bomb finally destroyed it during the Blitz.

Morbid curiosity has always been with us, of course, from Neanderthal funerary rites to medieval memento mori, but a recent spate of high-profile collections has made death particularly trendy of late. Besides von Hagens’s dubiously “useful” “Body Worlds,” the superstar artist Damien Hirst (with a new exhibit at the Tate Modern, London) covers human skulls in diamonds, chain-saws pickled cows in half, and generally displays death vitrines in a cheeky (and profitable) fashion. In Chicago, the biggest exhibit ever mounted at the Cultural Center was Richard Harris’s sprawling “Morbid Curiosity.” It contained more than 500 objects from all over the world, including a skull table, a giant bone chandelier, and classic vanitas paintings.

“I see beauty in the ugly,” Harris told me. “For some unexplained reason, I have always been attracted to the unusual, the uncomfortable thing, as well as the beautiful thing and their juxtaposed contrasts.”

When I asked Harris why he collects death, he grew philosophical, saying, “I am 74 years old and in good health, but I do realize that the majority of my life is behind me. We are all born to die—when, where, or how are the only variables. During the building of the collection, my own thoughts of mortality have changed. I believe that the way most people in our culture reject and hide from the thought of their own death and also any reference to death in general is uncaring.” So, Harris sees his collection as a way of reacquainting us with death and humanizing it.

Artists and literati have taken notice of the growing cultures of the macabre, raising them from the underground, so to speak, with recent conferences, courses, and books. Andrea Baldeck’s stunning new photography book of macabre images from the famous Mutter Museum has just been published by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Baldeck’s Bones, Books and Bell Jars (2012) transforms twisted vertebrae and embryonic disasters into fine art. And the art historian Paul Koudounaris performs a similar photographic transformation on European ossuaries and charnel houses in his exquisite Empire of Death (Thames and Hudson, 2011).

Standing in Koudounaris’s Los Angeles home, which is bursting with disturbing taxidermy and skeletal fragments hanging from the ceiling, I asked him if he saw beauty in the grotesque. “Cliché to say, but true,” he responded, “beauty is where one finds it. Part of the point of my book was to try to stress that the bone-decorated sites were not intended as frightful, but glorious.”

Like Harris, Koudounaris suggested that our culture sees death as disgusting and alien because we deny its inevitability. In a pre-Cartesian world, the body (even the dead body) was more valued as a source of the self. The unique person was manifested in the public body, and posthumous celebration of flesh and bone was enacted more affectionately. Plus, you might get your body back during the resurrection of the dead.

When I asked Koudounaris if recent artistic and academic interest in death was building into a cultural renaissance of the macabre, he seemed skeptical about the impact of such boutique interests. “I think the current fixation comes from it being hidden away, being made into something secret, unwanted, or taboo,” he said. “We are going to need a lot more than collectors, artists, and theorists before we can ever get to the point that the dead are drawn as close to the living as they once were.”

A provocative and fascinating collection of essays called Controversial Bodies: Thoughts on the Public Display of Plastinated Corpses, was published last year by the Johns Hopkins University Press. A few years ago, such a work would have consisted of a slush of postmodern English-professor bafflegab. But instead, the editor, John D. Lantos, brings together a refreshingly diverse set of voices and perspectives. Bioethicists, professors of medicine, psychiatrists, art historians, and theologians all meditate on the uncertain meaning of the macabre anatomical carnival.

One of the most interesting questions Controversial Bodies wrestles with is this: In a post-religious culture, what are the criteria of “decorum” and “dignity”? In a values melting pot like ours, an officially secular culture, when are we crossing the line of decency? Or is there no such line?

In the opening sequence of David Lynch’s haunting masterpiece The Elephant Man (1980), before we’ve met the deformed John Merrick, we find an aristocratic gentleman chastising the lowly carnival barker. “This exhibit degrades everyone who sees it!” And the carny retorts, “But he’s a freak. How else will he make a living?” To which the exasperated gentleman complains, “Freaks are one thing, but this is different. This is monstrous.” When are we educated and edified, and when are we degraded by taboo displays?

According to Lantos, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri at Kansas City and director of the bioethics center at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, similar objections have been leveled against von Hagens and other displayers of death. A German rabbi compared the public display of plastinated corpses to the Nazis’ skin lampshades, and a Catholic statement from the Vancouver archdiocese said, “The concept of the exhibit runs counter to Roman Catholic theology and our belief in the dignity of the human body, which we hold to be created in God’s image.”

In response to the age-old charge of obscenity, macabre collectors can try to outdo the theologians at their own game. From Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731) to von Hagens, purveyors of morbid flesh have argued that flayed bodies reveal the beautiful ingenuity of the Creator’s beneficent design. The taboo collection is justified not just on educational grounds but also on the grounds of spiritual edification. Nothing proves God’s existence, apparently, like an awe-inspiring display of the anatomized Imago Dei.

There seems to be something disingenuous in this pious argument for macabre display, especially when the feelings of awe are often equaled by feelings of disgust and revulsion. Moreover, most historical anatomical collections, like John Hunter’s, contained one physiological aberration after another (e.g., conjoined twins, hydrocephalics, etc.) and hardly signaled the engineering acumen of the Creator. No doubt the “designer defense” of morbid curiosity is actually just a spike against censorship. But what about these psychological toggles between the sublime and the gross?

Joanna Ebenstein, an artist and curator in New York, thinks von Hagens and his ilk have the emotional or psychological recipe all wrong. Like Richard Harris, Ebenstein sees morbid display as part of a nostalgic and almost reverential aesthetic. Maven of the beautiful grotesque, Ebenstein runs the highly influential blog Morbid Anatomy, and curates the Observatory Room lecture series in Brooklyn. The successful macabre must, according to Ebenstein, walk a razor’s edge between the crudely sensational and the graceful. “My working theory on this idea is that artifacts that flicker on the edges of death and beauty—or any other categories that seem to be in binary opposition—create a certain frisson, an ontological confusion,” she said. “I think for some people this confusion and flicker creates pleasure, for others anxiety, and for some, an enjoyable mixture of the two. I definitely find that frisson very exciting.”

Her Brooklyn Observatory Room has become ground zero for hipster artist fascination with 18th-century wax medical models, teratology jars, rogue taxidermy, and weekly lectures about the nature of curiosity, the history of anatomy, Freud’s theory of the uncanny, and practical mummification techniques.

On any given evening, you’ll find Ebenstein hosting an anthropomorphic taxidermy class, wherein bohemians (mostly women!) from all over New York converge to stitch together stuffed squirrels, chicks, and rabbits, posing them in ironically humorous tennis matches, tea parties, and other dioramas and shadowbox displays. Popular workshops teach contemporary crafters to skin rodents and curate them in the style of the great Sussex collector Walter Potter (1835-1918).

In addition, Ebenstein oversees a contemporary freak-show conference every year at Coney Island, called “The Congress of Curious People.” The conference is part scholarly analysis of macabre spectacle and part esoteric and bizarre performance—complete with disabled “freaks,” sword-swallowers, bearded ladies, fat men, and miscellaneous Barnum-style humbug.

Many artists, medical historians, bibliophiles, and edgy intellectuals have gravitated to Ebenstein’s curatorial mission. In part because the whole community celebrates the nostalgic predigital world of Victorian bell-jar aesthetics, but also because of the patient (almost obsessive) emphasis on craft that one finds in rogue taxidermy, wax anatomy, and specimen preparation. Craft was lost twice in recent memory—first, in the age of mechanical and digital reproduction, and second, with the rise of postmodern theory-laden art-school education. Over the last few decades, skilled artisans were alienated from institutional arts and humanities programs because apprenticeship was abandoned in favor of fancy talk—the dreaded conceptual turn.

The new subcultures of macabre collecting seek to enclose death and other curiosities in vitrines as a kind of rebellion—a demand for the thing in itself and not just the “discursive” and the digital representations of our contemporary simulacrum. Death is the ultimate spin-free zone and can be curated only so far, but it does give a bracing existential smack to our otherwise highly distracted population.

“For so long, it has been taboo to talk about or look at images of death,” Ebenstein explains. “I used to liken our attitudes toward death to the Victorian attitudes to sex; something that exists in the shadows but must not be spoken of. And of course, when something is suppressed in mainstream culture, it takes on perverse flowerings in other forms. I subscribe to Carl Jung’s notion about art, that an important role of the artist in society is to excavate and express the shadow side—the suppressed material of conventional society—in order to right the greater balance.”

In lieu of high-culture engagement with death—like rituals, museums, fine arts, and humanities—we have what Ebenstein calls a “trash-heap of youth subcultures and bad television.” The most important human mystery—our finitude—is often relegated to adolescent heavy-metal and goth cultures, or lowbrow torture-porn horror movies.

The new morbid curiosity, however, may be a pendulum swing back toward the sublime and the philosophical—a new secular foray into the morbid territory that religion previously charted. One way to avoid deeper engagement with death is to paint it entirely from the crude palette of emotions like disgust and fear. We’ve already got plenty of that kind of “morbid” in popular culture. But awe and wonder need to be restored to our experience of death, and we’re not sure how to do it in a post-religious culture.

Ralph Waldo Emerson thought that nature could be appreciated better when it was curated in a wonder cabinet. Curating nature allowed just enough distance for philosophical reflection, and just enough immediacy for authentic communion. Perhaps the new death cabinets can provide us the same balance for a more healthy confrontation with our own mortality.