On the first day of the spring semester, which now seems a lifetime away, I handed out index cards and asked students to respond to the usual suite of getting-to-know-you questions: name, hometown, major. But this time I also tried something new — I asked them to write a short paragraph about their own academic values and strengths.

“What are you good at in school?” I asked. “What do you care about in terms of your academic work? Do you love to participate in class? Are you a good leader on group projects? This is an English class, but maybe your strength is with statistics or math. If so, tell me about it. If I know about what you’re good at, maybe we can find a way for you to use it in this course.”

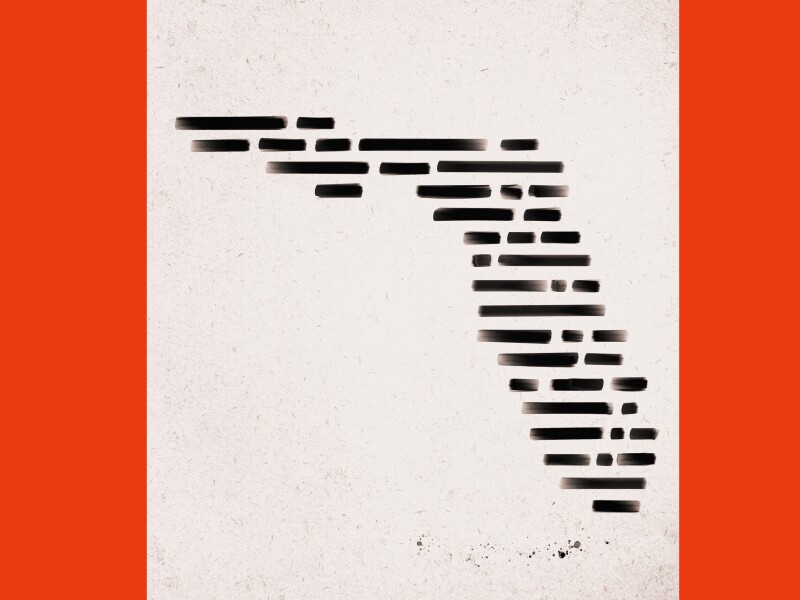

As colleges and universities have struggled to devise policies to respond to the quickly evolving situation, here are links to The Chronicle’s key coverage of how this worldwide health crisis is affecting campuses.

That was my quirky adaptation of a classroom activity known as a “values affirmation” — i.e., asking students to write about their most important personal values. Many studies in a mix of fields have demonstrated that values-affirmation exercises boost academic performance and persistence in a course, especially of students who are traditionally underrepresented in higher education or in specific disciplines. For instance, in a famous 2010 study — published in Science magazine — a pair of brief values-related assignments largely knocked out the usual performance gap between men and women among a group of students in an introductory physics course, compared with a control group who didn’t do the exercises.

In a recent Chronicle essay on closing the completion gap, David Gooblar provided a concise overview of values-affirmation studies. Different theories have been proposed as to why, and how, these exercises are so effective, and if I were writing this a few months ago, I would have run through those rationales for you. But the Covid-19 pandemic means we are in another place right now.

I’m not making any kind of formal study of how my version of a values affirmation influenced my students; perhaps I will in some future semester. But whatever effect it might have had on them, I can tell you that it had a profound effect on me.

Well before the global pandemic upended higher education, this brief exercise gave me an entirely new view of my students. I learned how hard they worked at their studies, how smartly they schedule their homework time, how carefully they balance coursework with sports and extracurriculars. I realized how proud they were of their ability to work well in groups, participate in discussions, or tutor their peers. I read with joy how many of them love to write outside of classwork.

When I flipped through their notecards in my office after class, all I could think was: What an incredible blessing to work with such hard-working and talented students. I felt so fortunate. And that perspective brought me a wellspring of fresh enthusiasm for a course that I had taught many times before, and for students whom I might otherwise have viewed as just another group of undergraduates filling the seats.

Just a few weeks ago, I had a second version of that epiphany. Amid all of the stress of moving my course quickly online, I was graced with another opportunity to view my students with eyes of gratitude and affirmation. Re-seeing them — midway through an impossible semester — has kept alive the passion I feel for the course and for their success in it.

It happened the second time via the simple mechanism of our course discussion board. Shifting online meant that weekly writing exercises that would have been done in class turned into discussion-board posts about reading assignments. Students have to complete a certain percentage of the prompts, but I asked everyone to do the first one just so we all could make sure we got the technical aspects of it right.

As I read through that first set of posts, I felt the same sense of joy and wonder as I had experienced reading their notecards. Although I try to engage as many students as possible, I usually only hear from half of my 27 students in a face-to-face discussion with the entire class. In a 50-minute class, which usually includes a mini-lecture from me, there just isn’t time for everyone to speak.

But when I prompted them on the course discussion board to write about George Orwell’s essay “A Hanging” — identifying and analyzing a key quote from the text — an incredible array of insights emerged. I learned more about that essay from their posts than I had from years of in-person class discussions. Students who rarely spoke in class highlighted subtle word choices, pointed to key images, and wrote thoughtfully about Orwell’s conflicted relationship to British imperialism.

The notion that online courses can provide avenues for greater participation than a traditional classroom — especially among quieter students or others who might feel intimidated about participating in person — will be a familiar one to anyone who already teaches online regularly. And my point here is not to argue for or against the mechanics of values affirmations or the virtues of class participation online versus face to face.

Instead, I’ve drawn a different lesson from those two very different writing exercises, used in two very different types of “classrooms” this semester: I need to work much more actively to figure out the assets my students bring to class, and how they can use those skills in class.

As college faculty members, we can easily fall into the trap of viewing our students primarily from a deficit-based perspective, rather than an asset-based one. They come to class, after all, because they lack something that we can provide: knowledge, skills, values, qualities. They have deficits we can help them to overcome.

On the first day of the semester in English composition, for example, I give my students a quick diagnostic writing exercise. When I read through their papers after class, what initially stands out to me are the problems — all of the gaps and holes and mistakes I need to focus on over the course of the semester.

Decades ago the Brazilian writer Paulo Freire famously critiqued the “banking” model of education in his book, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Educators, he argued, should not view knowledge as something we deposit in the heads of our passive students. I have wholeheartedly embraced that critique for my entire teaching career, just as I suppose many of you have.

But I’ve learned this semester that I have a lot more work to do when it comes to putting my convictions into practice — incorporating them into the actual structure and activities of my courses.

My thoughts on how I will do that are early and evolving, as is to be expected during this singular semester. But in the whirlwind of shifting life online, and treading water with my teaching and administrative responsibilities, it’s been a welcome intellectual relief to reflect, even for just a few moments, on what I can learn from this experience about my teaching for the future.

I don’t know what form my teaching and learning will take in the months ahead. But there is work yet to be done, and that this experience has lessons of value has been exactly what I have needed to keep my face forward and spirit alive during this crisis.