Many colleges have published iPhone apps in the last few years that allow people to get campus news, maps, and other information on Apple’s popular smartphones. Then some colleges found they also needed to develop a version for phones running Google’s competing Android system. And some built apps for BlackBerrys as well.

But at least a few colleges are now reconsidering the wisdom and the expense of building all those mobile apps. As the mobile Internet continues to grow at an astounding pace, those colleges are shifting their attention from stand-alone applications that can be downloaded from an app store to mobile-optimized versions of their Web sites.

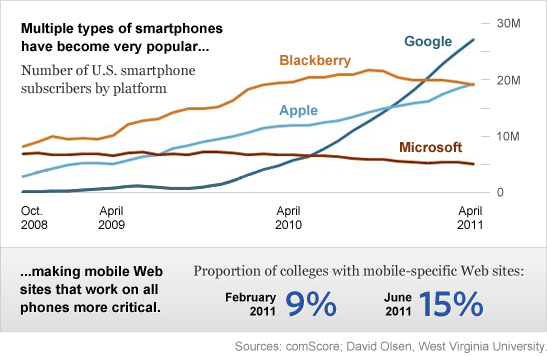

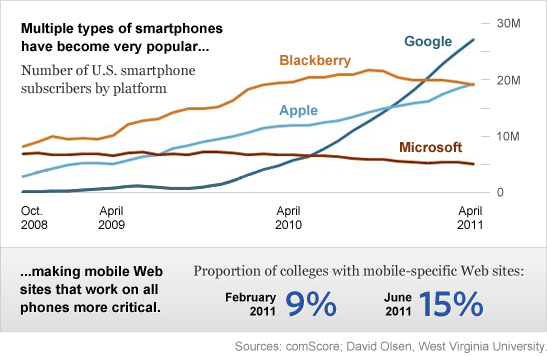

Multiple types of smartphones have become very popular, making mobile Web sites that work on all phones more critical.

Think m.college.edu, not iCollege.

The distinction between a mobile Web site and a mobile app might seem technical. But which one colleges prioritize—and some are pursuing both—will affect how much they spend on development, how effective their offerings will be, and how much they rely on vendors like Blackboard.

The University of California at San Diego, one of the first public universities to offer a mobile application, will end its mobile-application contract with Blackboard next year, according to Brett Pollak, director of the campus Web office. Instead, the college will soon start directing all mobile users to a version of its Web site, m.ucsd.edu.

Several new open-source software projects seek to help colleges create mobile Web sites, contrasting with a previous wave of software that helped them build mobile apps. One of those projects, from a team at the University of California at Los Angeles, has already been adopted at four University of California campuses, including UCLA.

College officials who favor mobile Web sites say that developing apps is getting too expensive. It can require creating and updating multiple versions of a single program, one for iPhones and another for Android phones, for instance. By contrast, a single mobile Web site can work with all kinds of devices, potentially lowering development costs.

Last month developers at the University of California estimated, using a rough calculation, that the system will save about $1-million in staff time each year by using UCLA’s mobile framework rather than trying to build downloadable applications.

Bradley C. Wheeler, chief information officer at Indiana University, argues that offering mobile campus services solely through a stand-alone application is becoming unsustainable. “We can declare a lot of victory for the first chapter in mobile,” says Mr. Wheeler, who is helping to start another Web-focused framework, Kuali Mobility Enterprise. “But there’s a lot of what we learned in the first chapter that will not scale in the next chapter.”

A ‘Natural Trend’

Releasing a mobile application requires getting all departments involved to release their data and stick to the same schedule, which can be a challenge, says William Allison, director of campus technology services at the University of California at Berkeley. Mobile Web sites can be produced in a way that more closely mirrors the decentralized structure of most colleges’ technical staff, he says.

“It’s actually a paradigm that works well in a university,” Mr. Allison says. “We’re not a top-down type of organization.”

The conclusions of those colleges are far from universal, and most colleges are not exactly pouring resources into building mobile Web sites. Research by David Olsen at West Virginia University shows that roughly 15 percent of colleges have a top-level Web site designed for mobile devices, up from roughly 9 percent in February.

Some observers, including Mr. Olsen, believe that colleges will actually need both mobile formats. “Guess what, you’re going to be doing everything, you’re going to be supporting everything, and that’s the nature of mobile,” Mr. Olsen says.

Supporters of mobile applications point out that mobile Web sites have limitations of their own. Many look less polished than their native cousins, and they can’t typically coordinate with all of the features of a mobile device, such as a camera. They also cannot be promoted in popular online marketplaces like Apple’s App Store.

Kayvon Beykpour, vice president of Blackboard Mobile, says the focus on mobile Web sites is an “obvious, natural trend” as more colleges recognize the importance of reaching people on mobile platforms. “It so happens that mobile Web is the most economical,” he says. “It’s clearly the easiest way to do it.”

But Mr. Beykpour says mobile applications are worth it. Colleges without one will miss reaching a critical group of tech-savvy users who “10 times out of 10" prefer downloading an application over using a mobile Web site, which serves the “everyone-else bracket,” he says. Mobile applications can also take advantage of the latest features of smartphones and tablets.

“That’s where we think the excitement is, that’s where we think the innovation is,” he says.

For instance, he says, Blackboard plans to release an augmented-reality application in the fall to help people discover interesting places on college campuses. When users point their phones’ cameras at a campus landmark, for instance, the application will display information about the landmark on their screens.

“You can’t do that stuff on the Web,” Mr. Beykpour says. “You just can’t.”