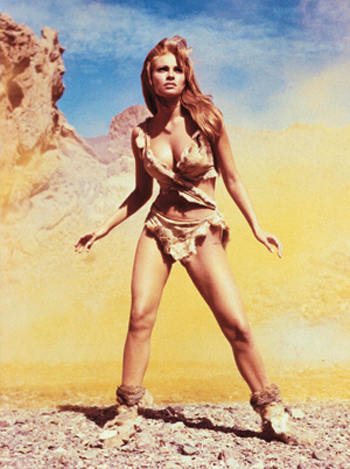

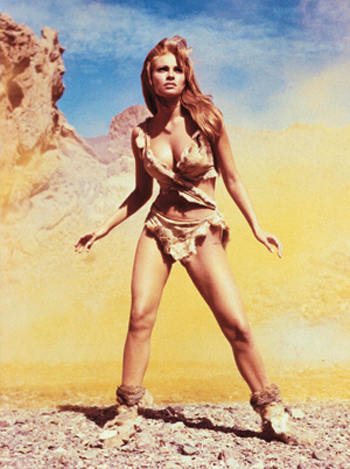

The Kobal Collection, Hammer

Raquel Welch in One Million Years B.C. (1966)

The first thing you have to do to study 4,000-year-old DNA is take off your clothes.

I am standing with Oddný Ósk Sverrisdóttir in the airlock room next to the ancient-DNA laboratory at Uppsala University, in Sweden, preparing to see how she and her colleagues examine the bones of human beings and the animals they domesticated thousands of years ago. These scientists are looking for signs of changes in the genes that allow us to consume dairy products past the age of weaning, when all other mammals lose the ability to digest lactose, the sugar present in milk. After that time, dairy products can cause stomach upsets. But in some groups of humans, particularly those from Northern Europe and parts of Africa, lactase—the enzyme that breaks down lactose—lingers throughout life, allowing them to take advantage of a previously unusable food source. Sverrisdóttir and her Ph.D. supervisor, Anders Götherström, study how and when this development occurred, and how it is related to the domestication of cows for their meat and milk. They examine minute changes in genes obtained from radiocarbon-dated bones from archaeological sites around Europe.

The first step is to extract the DNA from the bones. But when examining genes from other humans, you must avoid contaminating the samples with your own genetic material. Sverrisdóttir, a tall, blond Icelandic woman who looks like my image of a Valkyrie, at least if Valkyries are given to cigarette breaks and bouts of cheerful profanity, has brought a clean set of clothes for me to put on under the disposable spacesuitlike outfit I need to wear in the lab. I have to remove everything except my underwear, including my jewelry. Götherström says it is the only time he ever takes off his wedding ring. I don the clean outfit, followed by the white papery suit, a face mask that includes a transparent plastic visor over my eyes, latex gloves, and a pair of slip-on rubber shoes from a pile kept in the neverland between the lab and the outside world. Anything else that goes into the lab—a flash drive for the computer, say—cannot go back in once it has gone out, to prevent secondary contamination of the facility. Finally, I put on a hairnet and tuck my hair underneath.

We enter the lab, where the first thing we do is stretch another pair of gloves over the ones we just put on. Sverrisdóttir takes out a plastic bin of bone samples, each in its own zip-top bag. The bones themselves have been bleached and then irradiated with ultraviolet light to remove surface contamination. Before setting the bin on the counter, she wipes the surface with ethanol, followed by a weak bleach solution, and then with more ethanol. Apparently the saying that one can’t be too careful is taken literally in this lab. “We all have to be kind of OCD to do this work,” says Sverrisdóttir, smiling. Or at least I think she is smiling under her mask.

To obtain the DNA, the bones are drilled and the powder from the interior is processed so that the genetic sequences inside are amplified—that is, replicated to yield a larger amount of material for easier analysis. Some bones are more likely to be fruitful than others. Most of the samples are about 4,000 years old, but one of them is around 16,000 years old. It has already been rendered into powder, and I look at it closely, but it doesn’t seem any different from the others. One of the pieces is a flat section of skull, while others are sections of leg or arm bones, or a bit of pelvis. Sverrisdóttir and I wonder briefly who all these people were, and what their lives were like. The details of their experiences, of course, are lost forever. But the signature of what they were able to eat and drink, and how their diet differed from that of their—our—ancestors, is forever recorded in their DNA.

Other than simple curiosity about our ancestors, why do we care whether an adult from 4,000 years ago could drink milk without getting a stomachache? The answer is that these samples are revolutionizing our ideas about the speed at which our evolution has occurred, and this knowledge, in turn, has made us question the idea that we are stuck with ancient genes, and ancient bodies, in a modern environment. We can use this ancient DNA to show that we are not shackled by it.

Because we often think about evolution over the great sweep of time, in terms of minuscule changes over millions of years, when we went from fin to scaly paw to opposable-thumbed hand, it is easy to assume that evolution requires eons. That assumption makes us feel that humans, who have gone from savanna to asphalt in a mere few thousand years, must be caught out by the pace of modern life, when we’d be much better suited to something more familiar in our history. We’re fat and unfit, we have high blood pressure, and we suffer from ailments that we suspect our ancestors never worried about, like post-traumatic-stress disorder and AIDS. Julie Holland, a psychiatrist writing in Glamour magazine, counsels that if you “feel less than human,” constantly stressed and run-down, you need to remember that “the way so many of us are living now goes against our nature. Biologically, we modern Homo sapiens are a lot like our cave woman ancestors: We’re animals. Primates, in fact. And we have many primal needs that get ignored. That’s why the prescription for good health may be as simple as asking, What would a cave woman do?”

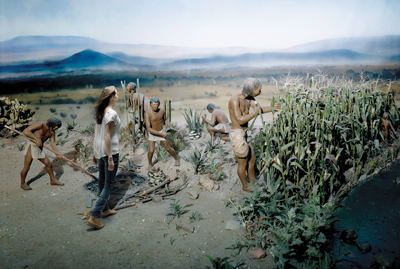

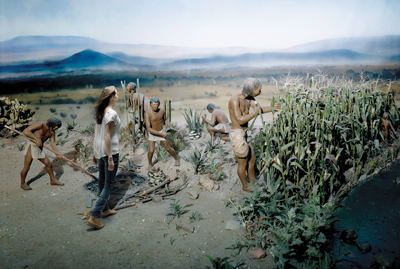

Engine Collective for The Chronicle Review, original image from Gianni Dagli Orti, Corbis

“Our bodies evolved over hundreds of thousands of years, and they’re perfectly suited to the life we led for 99 percent of that time living in small hunting and gathering bands,” writes a commenter on the New York Times health blog Well.

It’s hard to escape the recurring conviction that somewhere, somehow, things have gone wrong. In a time with unprecedented ability to transform the environment, to make deserts bloom and turn intercontinental travel into the work of a few hours, we are suffering from diseases our ancestors of a few thousand years ago, much less our prehuman selves, never knew: diabetes, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest that for the first time in history, the current generation of children will not live as long as their parents, probably because obesity and associated maladies are curtailing the promise of modern medicine.

Some of our nostalgia for a simpler past is just the same old amnesia that every generation has about the good old days. The ancient Romans fretted about the young and their callous disregard for the hard-won wisdom of their elders. Several 16th- and 17th-century writers and philosophers famously idealized the Noble Savage, a being who lived in harmony with nature and did not destroy his surroundings. Now we worry about our kids as “digital natives,” who grow up surrounded by electronics and can’t settle their brains sufficiently to concentrate on walking the dog without simultaneously texting and listening to their iPods.

To think of ourselves as misfits in our own time and of our own making flatly contradicts what we now understand about the way evolution works.

Another part of the feeling that the modern human is misplaced in urban society comes from the realization that people are still genetically close not only to the Romans and the 17th-century Europeans, but also to Neanderthals, to the ape ancestors Holland mentions, and to the small bands of early hominids who populated Africa hundreds of thousands of years ago. It is indeed during the blink of an eye, relatively speaking, that people settled down from nomadism to permanent settlements, developed agriculture, lived in towns and then cities, and acquired the ability to fly to the moon, create embryos in the lab, and store enormous amounts of information in a space the size of our handily opposable thumbs.

Given this whiplash-inducing rate of recent change, it’s reasonable to conclude that we aren’t suited to our modern lives, and that our health, our family lives, and perhaps our sanity would all be improved if we could live the way early humans did. Our bodies and minds evolved under a particular set of circumstances, the reasoning goes, and in changing those circumstances without allowing our bodies time to evolve in response, we have wreaked the havoc that is modern life.

In short, we have what the anthropologist Leslie Aiello, president of the renowned Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, called “paleofantasies.” She was referring to stories about human evolution based on limited fossil evidence, but the term applies just as well to the idea that our modern lives are out of touch with the way human beings evolved and that we need to redress the imbalance. Newspaper articles, morning TV, dozens of books, and self-help advocates promoting slow-food or no-cook diets, barefoot running, sleeping with our infants, and other measures large and small claim that it would be more natural, and healthier, to live more like our ancestors. A corollary to this notion is that we are good at things we had to do back in the Pleistocene, like keeping an eye out for cheaters in our small groups, and bad at things we didn’t, like negotiating with people we can’t see and have never met.

I am all for examining human health and behavior in an evolutionary context, and part of that context requires understanding the environment in which we evolved. At the same time, discoveries like those from Sverrisdóttir’s lab in Sweden make it clear that we cannot assume that evolution has stopped for humans, or that it can take place only ploddingly, with tiny steps over hundreds of thousands of years. In just the last few years we have added the ability to function at high altitudes and resistance to malaria to the list of rapidly evolved human characteristics, and the stage is set for many more. We can even screen the entire genome, in great gulps of DNA, looking for the signature of rapid selection in our genes.

To think of ourselves as misfits in our own time and of our own making flatly contradicts what we now understand about the way evolution works—namely, that rate matters. That evolution can be fast, slow, or in-between, and understanding what makes the difference is far more enlightening, and exciting, than holding our flabby modern selves up against a vision—accurate or not—of our well-muscled and harmoniously adapted ancestors.

The paleofantasy is a fantasy in part because it supposes that we humans, or at least our protohuman forebears, were at some point perfectly adapted to our environments. We apply this erroneous idea of evolution’s producing the ideal mesh between organism and surroundings to other life forms, too, not just to people. We seem to have a vague idea that long long ago, when organisms were emerging from the primordial slime, they were rough-hewn approximations of their eventual shape, like toys hastily carved from wood, or an artist’s first rendition of a portrait, with holes where the eyes and mouth eventually will be.

Then, the thinking goes, the animals were subject to the forces of nature. Those in the desert got better at resisting the sun, while those in the cold evolved fur or blubber or the ability to use fire. Once those traits had appeared and spread in the population, we had not a kind of sketch, but a fully realized organism, a fait accompli, with all of the lovely details executed, the anatomical t’s crossed and i’s dotted.

But of course that isn’t true. Although we can admire a stick insect that seems to flawlessly imitate a leafy twig in every detail, down to the marks of faux bird droppings on its wings, or a sled dog with legs that can withstand subzero temperatures because of the exquisite heat exchange among its blood vessels, both are full of compromises, jury-rigged like all other organisms. The mantid has to resist disease as well as blend into its background; the dog must run and find food as well as stay warm. The pigment used to form those dark specks on the mantid is also useful in the insect immune system, and using it in one place means it can’t be used in another. For the dog, having long legs for running can make it harder to keep the cold at bay, since more heat is lost from narrow limbs than from wider ones. These often conflicting needs mean automatic trade-offs in every system, so that each may be good enough but is rarely if ever perfect.

Engine Collective for The Chronicle Review, original image from Gianni Dagli Orti, Corbis

Neither we nor any other species have ever been a seamless match with the environment. Instead, our adaptation is more like a broken zipper, with some teeth that align and others that gape apart. Except that it looks broken only to our unrealistically perfectionist eyes—eyes that themselves contain oddly looped vessels as a holdover from their past. Wanting to be more like our ancestors just means wanting a slightly different set of compromises.

Recognizing the continuity of evolution also makes clear the futility of selecting any particular time period for human harmony. Why would we be any more likely to feel out of sync than those who came before us? Did we really spend hundreds of thousands of years in stasis, perfectly adapted to our environments? When during the past did we attain this adaptation, and how did we know when to stop?

If they had known about evolution, would our cave-dwelling forebears have felt nostalgia for the days before they were bipedal, when life was good and the trees were a comfort zone? Scavenging prey from more-formidable predators, similar to what modern hyenas do, is thought to have preceded, or at least accompanied, actual hunting in human history. Were, then, those early hunter-gatherers convinced that swiping a gazelle from the lion that caught it was superior to that newfangled business of running it down yourself? And why stop there? Why not long to be aquatic, since life arose in the sea? In some ways, our lungs are still ill suited to breathing air. For that matter, it might be nice to be unicellular: After all, cancer arises because our differentiated tissues run amok. Single cells don’t get cancer.

If we do not look to a mythical past utopia for clues to a way forward, what next? The answer is that we start asking different questions. Instead of bemoaning our unsuitability to modern life, we can wonder why some traits evolve quickly and some slowly. How do we know what we do about the rate at which evolution occurs? If lactose tolerance can become established in a population over just a handful of generations, what about an ability to digest and thrive on refined grains, the bugaboo of the paleo diet? Breakthroughs in genomics (the study of the entire set of genes in an organism) and other genetic technologies now allow us to determine how quickly individual genes and gene blocs have been altered in response to natural selection. Evidence is mounting that numerous human genes have changed over just the last few thousand years—a blink of an eye, evolutionarily speaking—while others are the same as they have been for millions of years, relatively unchanged from the form we share with ancestors as distant as worms and yeast.

What’s more, a new field called experimental evolution is showing us that sometimes evolution occurs before our eyes, with rapid adaptations happening in 100, 50, or even a dozen or fewer generations. Depending on the life span of the organism, that could mean less than a year, or perhaps a quarter-century. It is most easily demonstrated in the laboratory, but increasingly, now that we know what to look for, we are seeing it in the wild. And although humans are evolving all the time, it is often easier to see the process in other kinds of organisms.

Humans are not the only species whose environment has changed dramatically over the last few hundred years, or even the last few decades. Some of the work my students and I have been doing on crickets found in the Hawaiian islands and in the rest of the Pacific shows that a completely new trait, a wing mutation that renders males silent, spread in just five years, fewer than 20 generations. It is the equivalent of humans’ becoming involuntarily mute during the time between the publication of the Gutenberg Bible and On the Origin of Species. This and similar research on animals is shedding light on which traits are likely to evolve quickly and under what circumstances, because we can test our ideas in real time under controlled conditions.

It’s common for people to talk about how we were “meant” to be, in areas ranging from diet to exercise to sex and family. Yet these notions are often flawed, making us unnecessarily wary of new foods and, in the long run, new ideas. I would not dream of denying the evolutionary heritage present in our bodies—and our minds. And it is clear that a life of sloth with a diet of junk food isn’t doing us any favors. But to assume that we evolved until we reached a particular point and now are unlikely to change for the rest of history, or to view ourselves as relics hampered by a self-inflicted mismatch between our environment and our genes, is to miss out on some of the most exciting new developments in evolutionary biology.

At the same time that we wistfully hold to our paleofantasy of a world where we were in sync with our environment, we are proud of ourselves for being so different from our apelike ancestors. Animals like crocodiles and sharks are often referred to as “living fossils” because their appearance is eerily similar to that of their ancestors from millions of years earlier, preserved in stone. But there is sometimes a tone of disparagement in the term; it is as though we pity them for not keeping up with trends, as if they are embarrassing us by walking (or swimming) around in the evolutionary equivalent of mullet haircuts and suspenders. Evolving more recently, so that no one would mistake a human for our predecessors of even a couple of million years back, seems like a virtue, as if we improved ourselves while other organisms stuck with the same old styles their parents wore.

Regardless of the shaky ground on which that impression lies, we don’t win the prize for even most recent evolution; in fact, we lose by a wide margin. Strictly speaking, according to the textbook definition of evolution as a change in gene frequencies in a population, many of the most rapidly evolving species, hence those with the most recent changes, are not primates but pathogens, the disease-causing organisms like viruses and bacteria. Because of their rapid generation times, viruses can produce offspring in short order, which means that viral gene frequencies can become altered in a fraction of the time it would take to do the same thing in a population of humans, zebras, or any other vertebrate.

Evolution being what it is—without any purpose or intent—evolving quickly is not necessarily a good thing. Often the impetus behind rapid evolution in nonhuman organisms is a strong and novel selective agent: A crop is sprayed with a new insecticide, or a new disease is introduced to a population by a few individuals who stray into its boundaries. Those who are resistant, sometimes an extremely tiny minority, survive and reproduce, while the others perish. These events are not confined to crops, or even to nonhumans. Some estimates of death rates from the medieval outbreak of bubonic plague called the Black Death in Europe have gone as high as 95 percent.

Natural selection thus produces a bottleneck, through which only the individuals with the genes necessary for survival can pass. The problem is, that bottleneck also affects a lot of other genetic variation along with the genes for susceptibility to the insecticide or the ailment. Suppose that genes for eye color or heat tolerance or musical ability happen to be located near the susceptibility genes on the chromosome. During the production of sex cells, as the chromosomes line up and the sperm and egg cells each get their share of reshuffled genes, those other genes will end up being disproportionately likely to be swept away when their bearer is struck down early in life by the selective force—the poison or pathogen. The net result is a winnowing out of genetic variants overall, not just those that are detrimental in the face of the current selection regime.

The evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne, author of Why Evolution Is True, says that the one question he always gets from public audiences is whether the human race is still evolving. On the one hand, modern medical care and birth control have altered the way in which genes are passed on to succeeding generations; most of us recognize that we wouldn’t stand a chance against a rampaging saber-toothed tiger without our running shoes, contact lenses, GPS, and childhood vaccinations. Natural selection seems to have taken a pretty big detour when it comes to humans, even if it hasn’t completely hit the wall. At the same time, new diseases like AIDS impose new selection on our genomes, by favoring those who happen to be born with resistance to the virus and striking down those who are more susceptible.

Steve Jones, a University College London geneticist and author of several popular books, has argued for years that human evolution has been “repealed” because our technology allows us to avoid many natural dangers. But many anthropologists believe instead that the documented changes over the last 5,000 to 10,000 years in some traits, such as the frequency of blue eyes, means that we are still evolving in ways large and small. Blue eyes were virtually unknown as little as 6,000 to 10,000 years ago, when they apparently arose through one of those random genetic changes that pop up in our chromosomes. Now, of course, they are common—an example of only one such recently evolved characteristic. Gregory Cochran and Henry Harpending even suggest that human evolution as a whole has, on the contrary, accelerated over the last several thousand years, and they also believe that relatively isolated groups of people, such as Africans and North Americans, are subject to differing selection. That leads to the somewhat uncomfortable suggestion that such groups might be evolving in different directions—a controversial notion to say the least.

The “fish out of water” theme is common in TV and movies: City slickers go to the ranch, Crocodile Dundee turns up in Manhattan, witches try to live like suburban housewives. Misunderstandings and hilarity ensue, and eventually the misfits either go back where they belong or learn that they are not so different from everyone else after all. Watching people flounder in unfamiliar surroundings seems to be endlessly entertaining.

But in a larger sense, we all sometimes feel like fish out of water, out of sync with the environment we were meant to live in. If gnawing on that rib or jogging barefoot through the mud is therapeutic, enjoy. But know that should you wish to join us, the scientific evidence will gladly welcome you to the 21st century, in all its inevitable anxious uncertainty.