The Parent Loan Trap

More than a decade after Aurora Almendral first set foot on her dream college campus, she and her mother still shoulder the cost of that choice.

Ms. Almendral had been accepted to New York University in 1998, but even after adding up scholarships, grants, and the max she could take out in federal student loans, the private university—among the nation’s costliest—still seemed out of reach.

One program filled the gap: Aurora’s mother, Gemma Nemenzo, was eligible for a different federal loan meant to help parents finance their children’s college costs. Despite her mother’s modest income at the time—about $25,000 a year as a freelance writer, she estimates—the government quickly approved her for the loan. There was a simple credit check, but no check of income or whether Ms. Nemenzo, a single mom, could afford to repay the loans.

Ms. Nemenzo took out $17,000 in federal parent loans for the first two years her daughter attended NYU. But the burden soon became too much. With financial strains mounting, Ms. Almendral—who had promised to repay the loans herself—withdrew after her sophomore year. She later finished her degree at the far less expensive Hunter College, part of the public City University of New York, and went on to earn a Fulbright scholarship.

Today, a dozen years on, Ms. Nemenzo’s debt not only remains, it’s also nearly doubled, with fees and interest, to $33,000. Though Ms. Almendral is repaying the loans herself, her mother continues to pay the price for loans she couldn’t afford: Falling into delinquency on the loans had damaged her credit, making her ineligible to borrow more when it came time for Ms. Almendral’s sister to go to college.

Ms. Nemenzo is not alone. As the cost of college has spiraled ever upward and median family income has fallen, the loan program, called Parent PLUS, has become indispensable for increasing numbers of parents desperate to make their children’s college plans work. Last year the government disbursed $10.6-billion in Parent PLUS loans to just under a million families. Even adjusted for inflation, that’s $6.3-billion more than it disbursed back in 2000, and to nearly twice as many borrowers.

A joint examination by ProPublica and The Chronicle of Higher Education has found that PLUS loans can sometimes hurt the very families they are intended to help: The loans are both remarkably easy to get and nearly impossible to get out from under for families who’ve overreached. When a parent applies for a PLUS loan, the government checks credit history, but it doesn’t assess whether the borrower has the ability to repay the loan. It doesn’t check income. It doesn’t check employment status. It doesn’t check how much other debt—like a mortgage or other student loans—the borrower is already on the hook for.

“Right now, the government runs the program by the seat of its pants,” says Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of two authoritative financial-aid Web sites. “You do have some parents who are borrowing $100,000 or more for their children’s college education who are getting in completely over their heads. Those parents are going to default, and their lives are going to be ruined, because they were allowed to borrow far more than is rational.”

Much attention has been focused on students burdened with loans through their lives. The recent growth in the PLUS program highlights another way the societal burden of paying for college has shifted to families. It means some parents are now saddled with children’s college debt even as they approach retirement.

Unlike other federal student loans, PLUS loans don’t have a cap on borrowing. Parents can take out as much as they need to cover the gap between other financial aid and the full cost of attendance. Colleges, eager to raise enrollment and help families find financing, often steer parents toward the loans, recommending that they take out thousands of dollars with no consideration as to whether they can afford it.

Overburdened Borrowers

When it comes to paying the money back, the government takes a hard line. PLUS loans, like all student loans, are all-but-impossible to discharge in bankruptcy. If a borrower is in default, the government can seize tax refunds and garnish wages or Social Security. What is more, repayment options are actually more limited for Parent PLUS borrowers compared with other federal loans. Struggling borrowers can put their loans in deferment or forbearance, but except under certain conditions Parent PLUS loans aren’t eligible for either of the two main income-based repayment programs to help borrowers with federal loans get more-affordable monthly payments.

The U.S. Department of Education doesn’t know how many parents have defaulted on the loans. It doesn’t analyze or publish default rates for the PLUS program with the same detail that it does for other federal education loans. It doesn’t calculate, for instance, what percentage of borrowers defaulted in the first few years of their repayment period—a figure that the department analyzes for other federal student loans. (Colleges with high default rates over time can be penalized and become ineligible for federal aid.) For parent loans, the department has projections only for budgetary—and not accountability—purposes: It estimates that of all Parent PLUS loans originated in the 2011 fiscal year, about 9.4 percent will default over the next 20 years.

But according to an outside analysis of federal survey data, many low-income borrowers appear to be overburdening themselves.

The analysis, by Mr. Kantrowitz, uses survey data from 2007-8, the latest year for which information is available. Among Parent PLUS borrowers in the bottom 10th of income, monthly payments ate up 38 percent of their monthly income. (By way of contrast, a federal program aimed at helping struggling graduates keeps monthly payments much lower, to a small share of discretionary income.) The survey data do not reflect the full PLUS-loan debt for parents who borrowed through the program for more than one child, as many do.

The data also show that one in five Parent PLUS borrowers took out a loan for a student who received a federal Pell Grant—need-based aid that typically corresponds to a household income of $50,000 or less.

When Victoria Stillman’s son got into Berklee College of Music, she couldn’t believe how simple the loan process was. Within minutes of completing an application online, she was approved. “The fact that the PLUS loan program is willing to provide me with $50,000 a year is nuts,” says Ms. Stillman, an accountant. “It was the least involved loan paperwork I ever filled out and required no attachments or proof.”

She decided against taking the loan, partly because of the 7.9-percent interest rate. Although it was a fixed rate, she found it too high.

Of course, Parent PLUS can be an important financial lifeline—especially for those who can’t qualify for loans in the private market. An iffy credit score, high debt-to-income ratio, or lack of a credit history won’t necessarily disqualify anyone for a PLUS loan. Applicants are approved so long as they don’t have an “adverse credit history,” such as a recent foreclosure, defaulted loan, or bankruptcy discharge. (As of last fall, the government also began disqualifying prospective borrowers with unpaid debts that were sent to collection agencies or charged off in the previous five years.)

The Education Department says its priority is making sure college choice isn’t just for the wealthy. Families have to make tough decisions about their own finances, says Justin Hamilton, a spokesman for the department. We “want folks to have access to capital to allow them to make smart investments and improve their lives,” Mr. Hamilton says. In the years after the credit crisis, department officials point out, other means of financing college—such as home-equity loans and private student loans—have become harder for families to get.

The department says it’s trying to pressure colleges to contain costs, and working to inform students and families of their financing options. “Our focus is transparency,” says Mr. Hamilton. “We want to make sure we’re arming folks with all the information they need.”

Colleges’ Tricky Role

Colleges rarely advise families on how much is too much. After a student’s own federal borrowing is maxed out, financial-aid offices often recommend large PLUS loans for parents.

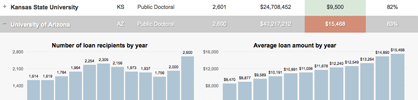

Using Education Department data, The Chronicle and ProPublica took a closer look at colleges where borrowers took out the highest average PLUS loan amounts per year. (See a breakdown of the top colleges at chronicle.com.) NYU ranked 11th, with an average annual loan of $27,305. The university generally gives students less financial aid than many of its peers do. Last year parents of NYU students borrowed more than $116-million through the PLUS program, the second-largest sum taken on for a single university, trailing only Penn State University’s $160-million.

“Our first suggestion is the PLUS loan,” says Randall Deike, vice president for enrollment management at NYU. Yet he has misgivings about the program. “Getting a PLUS loan shouldn’t be so easy,” he says.

Of the 25 institutions with the largest average PLUS loans, a third focus on the arts. Tenth on the list is the New York Conservatory for Dramatic Arts, a for-profit acting school. The school’s sticker price for the current year adds up to nearly $53,000 for a year’s worth of tuition, fees, room, board, and other expenses. Without an endowment, says David Palmer, the conservatory’s chief executive, the school can’t provide much financial aid—so families are often left to make difficult decisions about how much borrowing is too much. Ideally, families would have saved for college, according to Mr. Palmer, but often tuition payments come in the form of PLUS loans.

“It doesn’t make me feel great, truthfully,” Mr. Palmer says. “But then again, what can I do? We have to pay our bills.”

Last year, 150 parents borrowed for their children to attend the institution of 330 undergraduate students. Mr. Palmer knows that sometimes families borrow too much, and students have to drop out. “It makes me sick to my stomach,” he says. “Because they’ve got half an education and a mountain of debt.”

Still, he says, “I don’t know that it’s the institution’s responsibility to say we’ll take a glimpse of what your individual situation is and say maybe this isn’t a good idea.”

To the dismay of consumer advocates, some colleges lay out offers of tens of thousands of dollars in Parent PLUS loans directly in their financial-aid packages—often in the exact amount needed to cover the gap between other aid and the full cost of attendance. That can make it look like a family won’t have to pay anything at all for college, at least until they read the fine print. The offers are often included in financial-aid packages even for families who clearly can’t afford it.

“It is deceptive,” says Greg Johnson, chief executive of Bottom Line, a college-access program in Boston and New York. His organization’s counselors have seen firsthand how students and families can get confused: When Agostinha Depina got her financial-aid award letter from New York’s St. John’s University, her first choice, she was excited. But upon taking a closer look at the package with her counselor at Bottom Line, she realized that a $32,000 gap was being covered by a Parent PLUS loan that her parents would struggle to afford.

“It made it seem like they gave me a lot of money,” says Ms. Depina. In reality, “it was more loans in the financial-aid package than scholarship money.” Ms. Depina, 19, opted to go to Clark University, where she had a smaller gap that she covered with a one-year outside scholarship. A spokeswoman for St. John’s did not respond to requests for comment.

‘A Moral Dilemma’

There’s considerable debate among financial-aid officials about whether and how to include PLUS loans in students’ award letters. Some universities opt not to package in a loan that families might not qualify for or be able to afford. Instead they simply provide families with information about the program.

“We inform them about the different options they have, but we wouldn’t go in and package in a credit-based loan for any family,” says Frank Mullen, director of financial aid at Berklee. “To put a loan as part of someone’s package without knowing whether they’d be approved? I just wouldn’t feel comfortable with it.”

Others say it isn’t so simple. “This is one of those knives that cuts both ways,” says Craig Munier, director of scholarships and financial aid at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln.

“If we leave a huge gap in the financial-aid package, families could reach the wrong conclusion that they cannot afford to send their children to this institution,” says Mr. Munier, who is also chair-elect of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators. “The other side,” he says, “is we package in a loan they can’t afford, and they make a bad judgment and put themselves into debt they can’t manage. You can second-guess either decision.”

For parents in exceptional circumstances, colleges have some discretion to bypass the PLUS application process and give a student the additional amount of federal student loans that would be available in the case of a PLUS denial—up to $5,000. Those are judgment calls, says Justin Draeger, president of the aid administrators’ group.

Cases of a parent who is incarcerated or whose only income is public assistance are more straightforward, but the prospect of evaluating a parent’s ability to pay is fraught. Deciding to tell them what they can afford “leaves the schools in sort of a moral dilemma,” Mr. Draeger says.

But encouraging PLUS loans for parents who would struggle to repay them lets colleges shirk their own responsibility to help families with limited means, says Simon Moore, executive director of College Visions, a college-access program based in Rhode Island. “Colleges can say, ‘We want to enroll more low-income students,’ but don’t really need to step up and offer students good aid packages,” he says. PLUS loans “offer colleges an easy way to opt out.”

Middle-Class Struggles

Some parents who have borrowed through PLUS have found themselves working when they could be retired, and contemplating whether to pay off the debt by raiding their retirement nest eggs.

Galen Walter, a pharmacist, has put three sons through college. All told, the family racked up roughly $150,000 in loans, about $70,000, he estimates, in the Parent PLUS program.

Mr. Walter is 65. His wife is already collecting Social Security. “I could have retired a couple years ago,” he says, “but with these loans, I can’t afford to stop.” His sons want to help with the PLUS payments, but none are in the position to do so: One son is making only $24,000. Another is unemployed. The youngest is considering grad school.

Before the downturn, Mr. Walter says, he might have been able to sell his house and use the profit to pay off the loans. But given what his house is worth now, selling it wouldn’t cover the loan. With his sons in a challenging job market, he thinks he may be repaying the loans for at least a decade.

Many parents are more than willing to take on the burden. Steve Lance, 58, is determined to pay for the education of his two sons, whose time at private universities has left him saddled with $133,000 in Parent PLUS loans. (He also says he’s committed to paying for his sons’ federal and private student loans, which bring the total to $317,000 in debt.)

“The best thing I thought I can do as a parent is support them in having their dreams come true,” says Mr. Lance, a creative director who writes and speaks on advertising and marketing. “There’s no price tag on that.” Out of necessity, he has put some loans in deferment.

Often, students and families set their hearts on a specific college and will do whatever it takes to make it work, betting that the rewards will outweigh the financial strain.

That’s what happened with J.C., who asked that her name not be used. J.C. took out about $41,000 to help her daughter, an aspiring actress, attend NYU. A high-school valedictorian, her daughter could have gone to a public university in their home state of Texas debt-free, J.C. says. But the opportunities in theater wouldn’t have been the same. It had to be NYU.

“The night she got there she said, ‘Mom, this is the air I was meant to breathe,’” J.C. says of her daughter. J.C., 58, is divorced and makes about $50,000 a year. She anticipates PLUS loan payments of $400 to $500 a month, which she says she can handle. “I’ll never retire. I’ll work forever, that’s OK,” she says. Still, the hope is that her daughter makes it to the big time in her acting career: “If she’s really, really successful I’ll retire sooner rather than later,” J.C. says.

A Stopgap Solution

The Education Department’s recent change in how it defines adverse credit history—adding unpaid collections accounts or charged-off debt as grounds for denial—is meant to “prevent people from taking on debt they may not be able to afford while protecting taxpayer dollars,” Mr. Hamilton, the department spokesman, wrote in an e-mail message.

The change may result in significantly more Parent PLUS loan denials, according to Mr. Kantrowitz—and some financial-aid officers’ recent observations seem to bear that out. But new denials may actually involve the wrong people. After all, the tightened underwriting still examines aspects of credit history, not ability to repay. “It’s not going to make much of a difference for people who overborrow. It’s not going to prevent people from overborrowing,” Mr. Kantrowitz says. Instead the new policy may exclude borrowers who once fell behind on a debt, he says, but now pose little credit risk.

Borrowers who are denied can appeal the decision and still get the loans if they convince the Education Department that they have extenuating circumstances. Or they can reapply with somebody co-signing for the loan. It’s not yet clear how much the change in credit checks will alter the scope of the Parent PLUS program. Early tallies for the 2011-12 year show a modest dip in borrowing over the previous year, but the data are incomplete and won’t be fully updated for months.

For now, the Parent PLUS program is part of a stopgap solution to the complex problem of college affordability. And the factors that drive parents to borrow too much won’t be changing anytime soon.

Mr. Kantrowitz believes that the student-loan system is in need of much broader solutions. The current federal loan limits for undergraduates are arbitrary, he says, and not based on the type of program or a student’s estimated future earnings. More grant money could also help alleviate overborrowing, especially for low-income families.

“We need a complete overhaul of the student-loan system so there’s a more rational set of limits” to curb the debt problem, says Mr. Kantrowitz. The government can’t keep “magically sweeping it under the parent rug.”

We're sorry. Something went wrong.

We are unable to fully display the content of this page.

The most likely cause of this is a content blocker on your computer or network.

Please allow access to our site, and then refresh this page. You may then be asked to log in, create an account if you don't already have one, or subscribe.

If you continue to experience issues, please contact us at 202-466-1032 or help@chronicle.com