Ask any educated person what the placebo effect is, and almost all of them will be able to tell you. They will also accept, without any arm-twisting, that the placebo effect is real. After all, there is no real controversy around placebos — it’s well established that they work. And yet, any time I’ve suggested to an educated person that the placebo effect may be working on them — that they might as well be taking sugar pills for their colds instead of vitamin C — I get strenuous denials in response.

Many of us are ready to accept that placebos can work in general, just not on us. A similar dynamic exists with implicit biases.

Looking for inspiration on teaching or some specific strategies? David Gooblar, a former lecturer in rhetoric at the University of Iowa who is now associate director of Temple University’s Center for the Advancement of Teaching, writes about classroom issues in these pages. Here is a sampling of his recent columns.

Most of us now readily accept that behavior is often driven by unconscious attitudes and stereotypes. But suggest to people that they themselves may have implicit biases, and suddenly the defense mechanisms roar into effect. But we do have implicit biases — every one of us — and as faculty members, it’s imperative we try to take them into account.

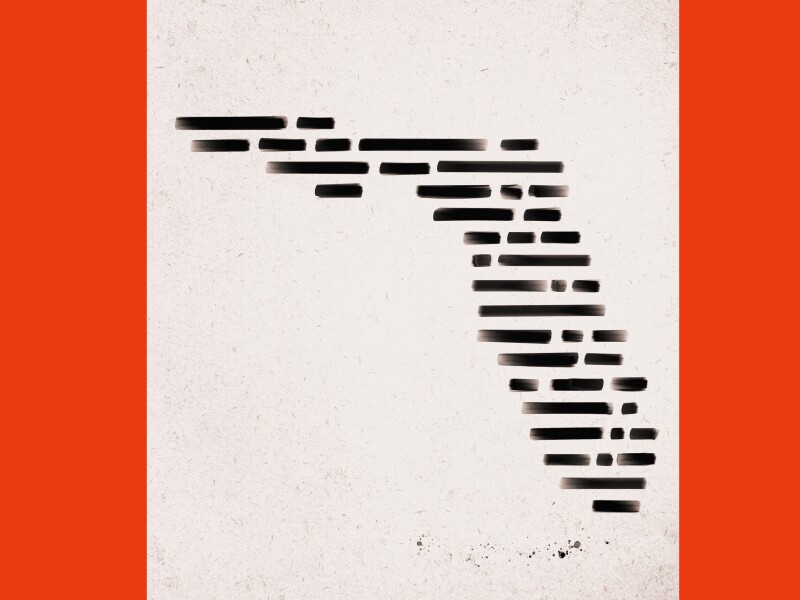

The challenge of confronting our own biases as teachers came to mind as I read news accounts this fall about the controversy over “the progressive stack.” A graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania reported being pulled from the classroom for using that teaching technique, which aims to offer students whose voices tend to be marginalized in class discussions a greater opportunity to speak.

In my own classroom, I often ask my students to imagine a world in which 80 percent of the national political leaders are men, 95 percent of the prominent business leaders are men, 70 percent of the established scientists and engineers are men, and 85 percent of the police officers are men. If you grew up in such a world, I ask students, what would your idea of an authority figure be? Wouldn’t it be natural — having seen positions of authority held mostly by men your whole life — to associate the masculine with the authoritative? Under those circumstances, wouldn’t you, all else being equal, see a man as more qualified than a woman?

Of course, this imagined world is our own. For Patricia G. Devine, a professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and director of its Prejudice and Intergroup Relations Lab, the repeated exposure to stereotypes is precisely how implicit bias is formed — and may hold the key to how it can be erased.

In work stretching over decades, Devine has put forward a theory that prejudice functions as a kind of habit. We get used to certain associations — say, that students from a marginalized group struggle academically compared with white students — and when we come in contact with a student from that group, our default attitude is to uphold the stereotype. Without conscious work to counteract this automatic “activation,” we assume the association is true.

As teachers, we set the tone for the classroom environment, modeling for our students what scholarly behavior should be like. Just as important, we function as institutionally-backed authority figures. We evaluate students, make judgments, create rules, and often decide who gets to speak and when. If we are serious about our responsibility to create a classroom environment in which every student has an equal opportunity to excel, we need to take a hard look at our own behavior. We have to take whatever steps are necessary to combat anything that might handicap our ability to be fair, including any implicit bias.

We get used to certain associations — say, that students from a marginalized group struggle academically — and when we come in contact with a student from that group, our default attitude is to uphold the stereotype.

The fact that implicit biases are implicit — that is, hidden even from ourselves — means that our perception of what is right may be off. Some employers who favor a white applicant over a black person with the same credentials don’t think they are prejudiced, and are unaware of their own bias. When such assumptions remain unconscious, they can deform our sense of fairness. As Devine notes in a 2012 article, “Implicit biases persist and are powerful determinants of behavior precisely because people lack personal awareness of them.”

That article details an experimental intervention, led Devine and her colleagues, to help subjects overcome implicit bias. In the years since, she has led many such interventions, both in and out of academe, and has been able to demonstrate remarkable success in reducing prejudicial behavior. In one such case, a series of gender-bias workshops at departments across the University of Wisconsin seemed to lead to an 18-percent increase in the hiring of female faculty members at those departments over the next two years.

We can’t all participate in one of Devine’s workshops. But in seeking to counter our own implicit biases, we can make use of the strategies she and her colleagues suggest, including:

- “Stereotype replacement” — in which you recognize and label your biased behavior or thoughts and replace them with nonprejudicial responses.

- “Counter-stereotypic imaging” — in which you imagine examples of people who defy the stereotypes of their groups.

- “Perspective taking” — in which you try to adopt the perspective of someone in a marginalized group.

Underlying all of those strategies is awareness: You have to be conscious of the existence of implicit biases, and the probability that you yourself may be influenced by them, before you can do anything about the problem. For all the controversy it has attracted, the “progressive stack” strikes me as an approach that attempts to respond to the problem of implicit bias in teaching. It developed in the context of Occupy Wall Street meetings. In the college classroom, the progressive stack involves looking for ways to create space for students from marginalized groups. If a number of students raise their hands to talk, you call on the marginalized students first, making sure that they get to speak. Without that conscious intervention, what you think of as a fair distribution of speakers may just be the furtherance of an unhealthy social dynamic: The privileged kids feel free to speak, while the marginalized students stay silent.

We communicate important values to our students by who and what we choose to give our attention to. Some things you can try in your own classroom: Look to highlight the work of people from marginalized groups in your field. Assign readings by women and people of color. Do what you can to model for your students what a more just version of your discipline might look like. Actively work against cultural stereotypes instead of passively assuming they’ll go away with time.

We may never be completely aware of our own implicit biases. But by assuming that we hold at least some of the pernicious stereotypes that our cultures have handed down to us, we can take steps to counteract them. As faculty members, we have a particular responsibility to work on this. Our role in the college classroom requires us to work toward a perhaps impossible ideal of equity. The first step is to open our eyes and look in the mirror.

David Gooblar is a lecturer in the rhetoric department at the University of Iowa. He writes a column on teaching for The Chronicle and runs Pedagogy Unbound, a website for college instructors who share teaching strategies. To find more advice on teaching, browse his previous columns here.